Basics

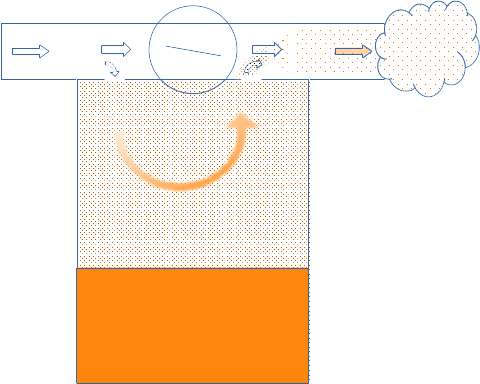

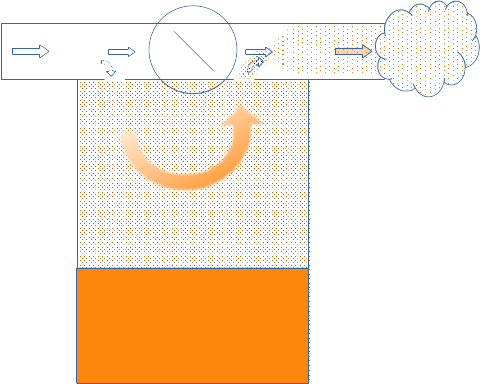

In order to be useable, it must be possible to deliver a volatile agent in a specific range of concentrations. In general, the vapours which form above most of the volatiles which have been used are far too potent for immediate use; they has to be diluted. One way in which this can be achieved is to split the gas flowing through the vaporizer, such that only a portion cones into contact with the volatile, the rest passing through a bypass channel. By altering the fractions passing along each route (in the figure below, by altering the resistance to flow through the bypass), the vapour concentration can be controlled. An example of this type of simple vaporizer is the Goldman.

As fresh-gas flows increase, more vapour is washed out of the chamber and the lower the concentration the vaporizer delivers. This can be corrected by ensuring that the vapour is always saturated. If this condition can be met, then the output of the vaporizer depends only on the splitting ratio.

To achieve this, the surface area from which the volatile can evaporate can be increased by the use of wicks (e.g. the String vaporizer).

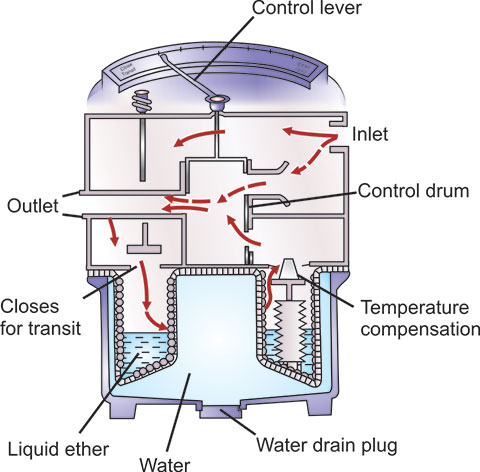

As the liquid in the vaporizer evaporates, its temperature will fall and with it the vapour pressure (be it saturated or unsaturated). This will reduce the performance of the device. This can be ameliorated by increasing the mass of the vaporiser, with the additional material acting as a heatsink. This approach was used in the EMO and OMV vaporizers, both of which have a water jacket.

The diagram of the EMO vaporizer also indicates a more sophisticated approach, that of temperature compensation. This makes use of an automatic adjuster which alter the spitting ratio depending upon temperature and this can be seen in the dismantled TEC 4 vaporizer in the RLH museum.